TRANSCRIPT:

It’s hard to put into words just what a game changer steam locomotives were. For thousands of years, the fastest any human could travel was on the back of a horse. Maybe a cheetah if you were brave enough.

What that means is traveling outside of your local area wasn’t really a thing. To simply travel to the next town was a multi-day excursion that required a team of people through bandit-infested forest paths.

But then, humans figured out that if you could harness the energy of water turning into steam, you could move pistons, that could move wheels, that could roll over steel tracks really fast, faster than any human had ever traveled, and for hundreds of miles.

Suddenly humans were traveling outside their local villages and seeing new places and hearing new ideas. This didn’t always go over well, but it was a really big deal!

But steam engines had a fatal flaw – and that was the extremely high pressures and temperatures that made them work. Which, if things went bad, they went very bad.

So bad they were eventually replaced. But like all technological dead ends, it took one spectacular disaster to really force things to change. And today, we’re going to talk about the one that ended the steam engine. The Hindenberg on rails.

On May 13, 1948, in the town of Chilicothe, Ohio, a farmer by the name of Dick Vincent was sitting on his porch when he heard an incredible explosion that shook the windows and knocked his wife’s sewing machine to the floor.

On hearing this, he knew two things, one, it came from the train tracks, so it was probably a train, and two, another train was due to come through any minute.

So he rushed off to the train tracks to find something from a Lovecraftian nightmare that had completely disabled the tracks and would threaten to derail the next train coming through.

Thinking quickly, he grabbed some signal flares and ran a mile up the road to warn the oncoming train. And he succeeded. The train came to a stop before it reached the explosion, which saved dozens of lives.

Dick Vincent. Hero.

It was only when he got back to the explosion site that Dick realized the true scale of the disaster. The locomotive had been blown to kingdom come, replaced by a mess of twisted metal pipes splayed out like steaming hot tentacles.

As he arrived, helpful townspeople swarmed the wreckage, a few of them pulling the engineer out of the cab, and laying his lifeless body beside the fireman on the side of the tracks, himself bloody and lifeless.

In a nearby yard, a doctor tended to the front brakeman, who was blinded by the accident and covered with second degree burns, his skin bubbling and peeling all over. He would later die at the hospital.

The event became known as the Boiler Explosion of C&O T-1 #3020 – which isn’t that catchy of a name but it was fairly consequential.

Because it happened at a time when steam train technology was waning as the engine of choice and stands as a bit of a dividing line between the steam age and the diesel age.

What happened on that fateful day in 1948 was unfortunately far too common on steam trains. Explosions happened all the time.

To understand why, it kinda helps to know how steam locomotives work, so I’ll give this a quick and dirty explainer.

A steam locomotive works by boiling water and then using the increased steam pressure to power pistons. Simple enough.

So to see how this works in a locomotive, you can divide it into three parts – the firebox, the boiler, and the smoke box.

The firebox is where they burn the fuel for the heat, often being coal or sometimes wood and later on, oil.

The boiler is basically a large cylindrical water tank turned on its side and filled with water.

And the smoke box is where the exhaust from the fire is collected and vented out.

Now you may be wondering why the exhaust is on the other side of the water tank. Well, that’s because there’s a series of dozens of pipes that pass through the boiler from the firebox to the smoke box, and they carry all that heat from the firebox with it.

That of course heats the pipes, which heats the water and causes it to boil. The steam in the top of the boiler builds up pressure, and that collects in the steam dome, where it gets piped down to the pistons.

Now that’s a very simplified version, they were able to get more energy out of the boiler by including superheaters, which direct the steam back through the boiler with dozens, even hundreds of smaller pipes that help heat the water even more and get even more pressure.

So in a steam engine, you’re constantly monitoring the water level in the boiler and adding the right amount when needed, you have to monitor the fuel to keep the heat at an even temperature, and of course accelerating and decelerating are done through manipulating those inputs.

So these boilers had to be at extremely high pressures to work, up to 300 psi, which by the way, also pressurized the water, and the higher the water pressure, the higher the boiling point, so the water in the boiler could get over 400 degrees Fahrenheit before it ever even boiled.

So yeah when things went wrong on steam engines, they went very, very wrong.

The explosion in Chilicothe likely happened because the water in the boiler fell too low during a hill climb.

Chilicothe sat on a bit of a plateau so the train had a slight uphill climb as it approached town, enough to make the water in the boiler slosh back, leaving the pipes exposed.

Oh, I should point out that sometimes train crews would run the boilers kinda low because that would create more steam faster. It’s like if you’re running a tea kettle, it boils a lot faster with one cup of water in it than four.

And they think the crew may have been doing that on the 3020 that day, and when the water slashed backwards the pipes overheated. The crew then added water too quickly, which hit the superheated bare pipes, and then explosively flashed into steam.

By the way, that metal was already weak from being superheated so when that extra steam pressure hit it, it just didn’t have a chance.

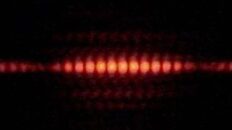

So yeah, when that boiler exploded, all those hundreds of tubes in the boiler splayed out creating this crazy Chthulu effect.

The Chillicothe accident was horrible, but it wasn’t all that rare.

Wikipedia records 53 boiler explosions in locomotives, claiming a total of 155 lives.

The earliest recorded incident happened in 1815, when 16 people were killed. The last incident was the 1995 explosion of a Gettysburg tourist train, which didn’t kill anyone but badly burnt the engineer.

1995 is kind of an outlier, really 1977 was the last boiler explosion from a commercial stream train, so we should stop counting there.

53 explosions between 1815 to 1977 comes out to about one every three years, with an average death toll of three people, which makes sense because it took three people to run it

Although the highest death toll was 26 people.

It happened in 1912 at a San Antonio rail yard. There was a strike going on at the time and it’s thought that a railway employee may have sabotaged a locomotive by messing with the safety valves, which caused a buildup of pressure.

This explosion was a monster, and it happened in a densely populated area so the damage was extra bad.

All buildings and equipment within 100 feet were demolished. Among the 26 killed were several who died in trapped buildings. In fact one of the victims was a woman named Mrs. B. S. Gillis, who died when the locomotive’s front end fell through her roof – and she was seven blocks away!

So was that what killed the steam engine? It was too deadly?

(react)

Eh?

I mean, clearly things can go very wrong but 155 deaths is a drop in the bucket compared to the thousands who died from derailments, collisions, and other locomotive disasters.

And if you want to keep going with it, those thousands are nothing compared to the 83,000 plus deaths on airplanes since 1970, and we consider that the safest form of travel – because proportionally it is.

By the way, maritime deaths make both trains and planes seem reasonable.

And of course all other forms of transportation don’t hold a candle to the 1.9 million people who die in automobile accidents EVERY YEAR.

Seriously, I’m surprised anybody leaves home.

So it wasn’t an unnecessarily high body count that doomed the steam engine, and it actually wasn’t performance that did it in, steam engines were actually more powerful than the diesel engines that replaced it.

It’s like how Beta actually had better picture quality than VHS but it still lost the video format war – there were other things at play here.

To start with, by the 1950s, steam engine technology was about as good as it was going to get, and to be fair, when you really dig into how these engines worked, they were marvels of mechanical engineering.

But the internal combustion engine was still on the rise, they had taken over the roads in automobiles and trucks, and the petroleum industry was big and powerful and everywhere by that point.

Also diesel was cheap. And it only took one driver instead of three, which also saved money. And it was easier to transport.

Yeah, I didn’t even talk about this earlier but part of the locomotive design was the tender cab that was pulled behind the locomotive and carried both water and coal to fuel it along the way. A diesel locomotive just needed a fuel car with diesel

It was also cleaner, believe it or not, it didn’t billow out giant clouds of steam and smoke from burning coal, and there were no giant pans of ash to clear out.

So it was mostly the economics of it and the simplicity of it but also… I think it’s fair to point out… No diesel engine explosions looked like this.

I mean… Kinda?

No, the Chilicothe explosion wasn’t the most consequential boiler explosion in history, but the Hindenberg wasn’t the deadliest airship disaster, either. It was just seen the most.

The Hindenberg disaster was caught on film and played in news reels all around the country, causing a wave of “Nopes” as far as the eye could see.

And this photo has some big nope energy.

And it wasn’t the only one. There’s actually a lot of boiler explosion photos out there, and they all kinda make me not want to get near one.

So in much the same way that the Hindenberg footage was the final nail in the coffin for airships, this photo was at least one of the last nails for steam trains.

Still, steam hasn’t gone away completely.

Tourist trains are still in operation, though under stricter guidelines than in 1995.

Internationally, some farms and factories still make use of steam trains. As of 2011, at least, sugar cane plantations in Java were making extensive use of steam to transport their product from the field; they also charged tourists to ride along

Some enthusiasts are even looking to build next-level steam technology for modern use.

One early effort was the 5AT Advanced Technology Steam Locomotive.

Proposed in 1998, studies were conducted all the way up to 2012, but they never were able to secure financial backing so it kinda never went anywhere.

Concepts for a solar-powered steam engine also exist. One was proposed for testing in Sacramento, California. So far as I can find, nothing came of it.

But I did manage to locate a 2022 paper out of the University of Michigan discussing the viability of a 1:8th scale solar steam train. Both of the Sacramento and UMichigan designs were to be fireless, meaning they’d either use stored steam or generate steam with fireless heat.

According to the UMichigan paper, a solar steam engine would have all the environmental advantages of a conventional solar, meaning no CO2 or Nitrous Oxide emissions.

Sounds cool, but considering full solar electric trains are already a thing, it doesn’t seem likely we’ll see steam added to the mix any time soon. At full scale, anyway.

So steam trains, that was a fun little rabbit hole, maybe some of you had seen this image and thought, ‘yikes, what’s that all about,’ well I thought the same thing. So I looked into it.

Add comment