World War 1 changed the world in countless ways, but one thing that doesn’t get talked about much is the way it spurred advancement in cosmetic surgery. With advances in medicine and the particular horror of trench warfare, thousands of soldiers came home with terrible facial injuries, causing them to be treated as pariahs. But thanks to the generosity and brilliance of surgeons and artists, great strides were made in returning their lives to normalcy.

TRANSCRIPT:

I’ve made the argument that World War 1 changed the world more than World War 2.

Yes, World War 2 killed more people and set up a Cold War that would dominate geopolitics for the next 50 years, but World War 1 ended the domination of multiple empires that had existed for hundreds of years.

And it set up a new regime of democratic nation states that so disrupted the world order that it led to a second world war to sort things out.

It also led to… this.

This is Jocelyn Wildenstein, a Swiss socialite who was known for her addiction to plastic surgery. By the 1990s, she’d had so many facial reconstructions that she took on the appearance of a cat, leading the tabloids to dub her the catwoman.

And she was in the tabloids A LOT.

She married a billionaire art dealer named Alec Wildenstein and was a fixture of New York’s high society in the 80s and 90s. They had a nasty divorce in 1999 when she caught him in bed with a 21 year old Russian model and at one point he apparently pulled a gun on her. Swell guy.

But she got her revenge, getting $2.5 billion in the divorce. And still managed to go bankrupt by 2018. She lived… an extravagant life.

And no, she didn’t spend ALL that money on plastic surgery but she did spend millions over the years.

We may never know exactly what demons drove her to do this to herself, but people get plastic surgery for a lot of reasons, often that have nothing to do with vanity, for some people with disfigurements, it gives them a chance to simply live a normal life, without people staring at them everywhere they go.

Which brings me back to World War 1.

World War 1 was the first fully mechanized war, which led to trench warfare.

And in trench warfare, the part of your body that’s exposed the most is your head. And the face that’s on it.

If you try to shoot at the enemy, you’ve got to pop your head above the trench, and now it’s a target. Even if you weren’t shooting, even if you were just stretching, it puts you in danger.

But even if you stay hunched down, if a high enough caliber projectile hits the top of the trench, it can send ground debris and wood flying at your face.

Mortar shells that land anywhere near the trench can send shrapnel at your face at high velocity, and don’t get me started on incendiary devices and chemical warfare like sulphur mustard gas.

The point is… Because of all this, tens of thousands of world war one vets returned home with horrifying facial disfigurements, which required a whole new kind of surgery.

Although it wasn’t entirely new…

Plastic Surgery History

In 1862, an American Egyptologist named Edwin Smith bought an ancient papyrus that was written in hieratic script, which is like a cursive form of heirogliphics, and it turned out to be a kind of medical textbook for treating war injuries.

And some of those injuries included head and face injuries, in fact, it had instructions on how to rebuild the nose. And it’s thought they were doing this as far back as 6000 BCE.

There’s also evidence that this was being done in India, too, and that they were even using skin grafts by 800 BCE.

The Romans used reconstructive surgery between 100 BCE and the 5th century AD, with some texts describing how to repair damaged ears.

The medical writer Aulus Cornelius Celsus even described using skin from other parts of the body.

And these were mostly to repair war wounds, not necessarily to improve one’s looks.

The first cleft palate operation was done in the United States in 1827 by Dr. John Peter Mettauer, who has come to be known as “America’s first plastic surgeon,” Though they didn’t call him that at the time because plastic wasn’t a thing yet.

Also can you imagine getting a cleft palate operation without anesthesia?

And in 1890, the first tummy tuck was performed in France.

- though I should point out that there is a fine line between cosmetic surgery and body modification, which many cultures engaged in, like the skull deforming of the Inca and Maya or the Chinese practice of foot binding.

You could argue that these are procedures that were done to fit the culturally agreed upon beauty standards of the time, though that’s not really what we’re talking about here.

So what are we talking about here?

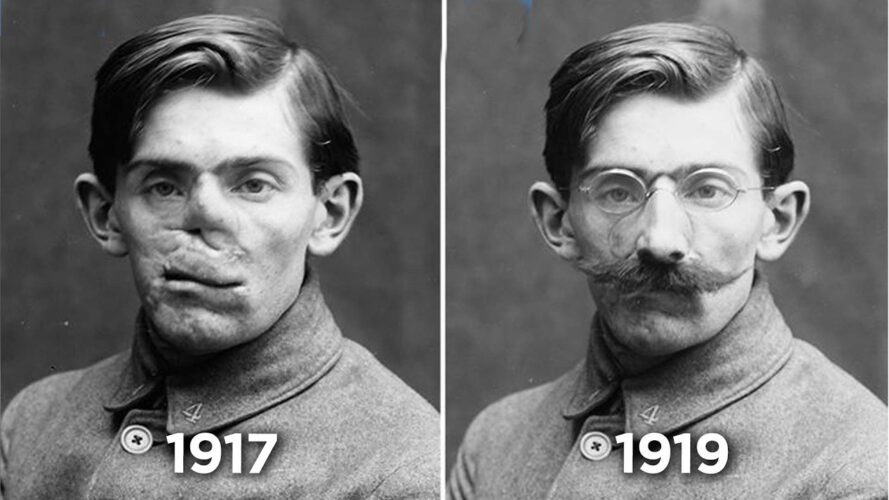

And in 1917, British soldier Walter Yeo is believed to be the first person to have plastic surgery, done by Sir Harold Gillies, who, stay tuned, we’ll get to later.

About Plastic Surgery

In professional parlance, Plastic surgery is used to describe a broad range of procedures that enhance or change a person’s body, either for aesthetic or corrective reasons.

Cosmetic and reconstructive procedures both fall under the term “plastic surgery.”

But really, when you hear “plastic surgery,” most people think of cosmetic procedures. Things like liposuction, breast surgery, or lip fillers.

According to a 2020 study, around 16 million cosmetic surgeries are done in the U.S. every year. I did the math, that’s 4.7% of the population.

And some of the most popular procedures are facelifts, eyelid surgery, and nose jobs.

Which makes sense, our faces are kind-of our calling card, it’s what people first look at, it’s what we identify with, it’s what they picture when they think of you. But also… let’s just be honest with ourselves, looks matter.

And I’m not just talking about in dating, that’s obvious, but professionally as well. People who are considered more attractive are more likely to get hired for jobs and on average make higher salaries. Even in the court system, more attractive people pay lower bail and get shorter jail sentences.

And it’s not just adults with certain social conditioning that brings this about, even babies have been shown to have a preference for people with more symmetrical faces and more feminine features.

I’ve talked before about the uncanny valley and how we really are hard-wired for faces – and our lizard brains just struggle to process faces that just don’t “look right.”

And it is very much a lizard brain thing. A neuroimaging study from 2019 showed that people have implicit negative biases against people with disfigured faces without knowingly harboring these biases.

Diminished neural responses in our anterior cingulate cortex showed that we’re less empathic toward people with disfigurements.

I mean there’s a reason why villains in movies are often portrayed with facial injuries or deformities, it’s like a cheat code to our lizard brains, making us instantly distrustful or fearful of that character.

Of course it’s not always about looks, personality goes a long way. People are attracted to confidence, and people with more attractive faces tend to project more confidence, partially because of how society perceives attractive faces, and partly because they generally have more confidence. Because they’ve always had a little bit of an advantage. And that confidence itself is more attractive.

So people with, let’s say abnormal facial features tend to have a disadvantage socially – doesn’t mean they can’t overcome them, just that they have to work harder than others.

Just one more thing to drive this point home, there are some photos of these World War 1 vets that I can’t show in this video – because I might get demonetized for using “shocking imagery.” That’s how strongly we enforce facial standards.

Plastic Surgery and WWI

So at the end of World War One, there were thousands of soldiers coming home with extreme facial disfigurements unlike any previous war we’ve ever seen, and instead of being welcomed as heroes, they were often treated like pariahs

Like imagine giving that much for your country, carrying with you all that physical and mental trauma, only to have children cry and women gasp at the sight of you like you’re some kind of monster.

Or as one U.S. doctor on the front said:

“Every fracture in this war is a huge open wound, with a not merely broken but shattered bone at the bottom of it.”

For example, one town in England painted some of its park benches blue, specifically for veterans to sit on. That was a code to warn people that anyone sitting on one would be too uncomfortable to look at.

But what may be even more upsetting is the fact often the people who were the most horrified to look at these soldiers… were the soldiers themselves.

A lot of hospital wards would ban mirrors so the patients couldn’t see themselves and go into shock.

As American surgeon Dr. Fred Albee said:

“It is a fairly common experience for the maladjusted person to feel like a stranger to his world. It must be unmitigated hell to feel like a stranger to yourself.”

With the number of men returning from the war with facial injuries, it was clear that something needed to be done so they could feel like their normal selves again.

One of those things was masks.

Francis Derwent Wood and Anna Colman Ladd

Anna Coleman Ladd was a successful sculptor who had solo exhibitions in New York, D.C., and Philadelphia between 1907 and 1915.

In 1917, she and her husband moved to France. That’s where she learned about Francis Derwent Wood, who made face masks at his Tin Noses Shop, also known as the Masks for Facial Disfigurement Department.

Wood was a British sculptor who worked on WWI soldiers to help them regain a sense of normalcy with their disfigured faces. The men were able to get jobs, live with their families, and feel like they were a part of society again.

As he told The Lancet in 1917:

“My work begins where the work of the surgeon is completed. When the surgeon has done all he can to restore functions… I endeavour by means of the skill I happen to possess as a sculptor to make a man’s face as near as possible to what it looked like before he was wounded.”

He would create the masks by first making a plaster cast of the person’s face. Then, he used clay or plasticine to show what the healed face would look like with its missing features replaced.

The final cask would be made from copper that was 1/32-inch thick. It was coated in silver and painted a cream color and topped with varnish for complexion.

Wood then matched the face’s contours, pigmentation, and texture to the patient’s skin. And if, say, an eye was missing, he might even paint it directly on the mask.

He’d also paint eyebrows onto the mask. For eyebrows, he used super thin metallic foil that he cut into strips, tinted, curled, and soldered into place.

But the masks weren’t comfortable, and the men had a love-hate relationship with them. It would remind them of what they used to look like.

Ladd was inspired by Wood’s work. She met with the American Red Cross and convinced them she could do the same thing he was doing. They helped her open her own place called the Studio for Portrait-Masks in 1918.

From the beginning, Ladd’s studio was a warm and inviting place. Ladd and her assistants would joke around with the men, trying to make them feel at home. As she said:

“They were never treated as though anything were the matter with them. We laughed with them and helped them to forget. That is what they longed for and deeply appreciated.”

Like Wood, she made masks of copper and silver, painting them as the patients wore them so she could match their skin colors correctly.

Glasses held the masks in place, but if a patient didn’t want to wear glasses, then she used a ribbon or thin wire to keep it attached to the face.

The whole process took about a month to complete.

A mask was considered a success when a patient could walk down a street in Paris without being noticed.

She had created around 185 masks by the end of 1919. She also donated her creative services, only charging $18 for a mask. That’s equal to about $375 today.

After the war ended, the Red Cross couldn’t afford to fund her studio anymore, so it closed.

She went back to the U.S., where she lived her life as an artist until she died at age 60 in 1939.

Mask Limitations

While the masks offered a somewhat sense of normalcy, there were some limitations to them.

For one, since they were made of thin copper, they were easily damaged. They weren’t durable and would eventually show signs of wear and tear.

They were also static. They didn’t restore a face’s function or movement.

Also, the masks only covered the damaged areas of a patient’s face, like the eye, chin, mouth, or nose. Even with a good paint job, you could still tell the person was wearing a mask.

Finally, the men would have to deal with aging, since their faces would grow older but their masks would stay the same age.

Over time, the difference between their wrinkled skin and the copper mask would become too noticeable. Not to mention the paint would flake off the masks, revealing the metal face underneath.

Metalface… hehe, that would make a good…

Sir Harold Gillies

Gillies studied medicine in England and specialized in ear, nose, and throat surgery before the war and then he served during the war in the Royal Army Medical Corps.

It was there that he met a French surgeon named Hippolyte Morestin (make fun of my pronunciation)

Dr. Morestin was kind-of the French army’s expert in face and jaw injuries and Gillies saw what he was able to do to not just repair these soldier’s faces but also reconstruct them. And how much it improved those soldiers’ lives.

And he realized that with his own background in ear, nose, and throat surgeries, that’s something he could do for the British Army.

So he convinced the army that there was a need for this kind of special reconstructive care. And they agreed, setting up a unit under his command at Queen Mary’s Hospital in Sidcup, England.

There, he led a team of surgeons, nurses, and artists to find permanent solutions for these soldiers. And together they got creative and pioneered techniques that are still in use today.

They took skin and cartilage from other parts of the body and built up areas that were missing tissue, he’d even use a patient’s rib bone to jaws and lobes and other structures on the face.

Perhaps most famously, he invented the “tube pedicle.” Which is kind-of gnarly to look at, but it’s cool.

So, a skin graft is obviously when you transfer skin from one part of the body to another, but the problem with skin grafts is getting the blood vessels to connect to the new tissue. Because if you don’t, it just dies and now you’ve got a patch of rotten skin, which is not ideal.

But with a tube pedicle, instead of just slicing a chunk of skin off to graft, you cut away a flap of skin, leaving one end of the flap connected to the original source of blood, and graft the other end to the place you’re grafting it to.

That way the grafted skin can maintain blood flow while it’s connecting to the blood vessels of the graft site, which takes a few weeks, but once it’s established, you snip the other end of the graft, and now you can use that skin to fix the spot that you’re working on.

It has a way higher success rate and cuts down drastically on infections.

Tube pedicles are used all the time in cosmetic surgery today, it was an absolute game changer, and it all started with Dr. Gillies’ treatment of world war one vets.

After the war, he practiced plastic surgery exclusively. And he actually got a lot of criticism for that early on. Cosmetic surgery was considered frivolous and not important work.

But he argued that it was important work that required craft and skills that genuinely improved the lives of his patients.

Plastic Surgery Today

And I think it’s safe to say that time has proven him right. An entire industry sprang up around his work that of course now is worth tens of billions of dollars.

And while plastic surgery still might be something that some people might scoff at, that fact is that at some point we’re all going to get some work done.

As we’re living longer, our skin will start doing a lot of unfortunate stuff, and that unfortunate stuff will need to be taken off.

Hell I had a minor skin cancer surgery right here that required a little reconstruction. And it probably won’t be the last.

But even plastic surgery just to enhance your attractiveness has it’s place, in terms of positive mental health.

Some studies have shown that people who undergo plastic surgery like Botox, breast augmentation, and rhinoplasty are more satisfied with their lives, even up to five years after their surgeries.

Of course the flipside exists, too, Other studies show that people often have negative feelings post-surgery, from everything including post-operative complications, relationships, and body dysmorphic disorder issues.

There are always going to be people who take it too far. But they deserve our empathy, not our derision.

Which brings me back to Jocelyn Wildenstein, who I found out while writing this that she just died a few months back in December. So, RIP Jocelyn. I’ll avoid making a joke about her having eight more lives.

Add comment